The Particles That Make the World Go Round

Eva Rexach

14 March 2019

At the upcoming Kosmopolis 19 we’ll talk about quantum physics and all the cultural, political and ethical implications of this science. To set the scene, we offer a timeline from the birth of quantum mechanics through to its presence in different areas of our daily lives, as well as a reminder of all the activities where you can enjoy The Quantum Story.

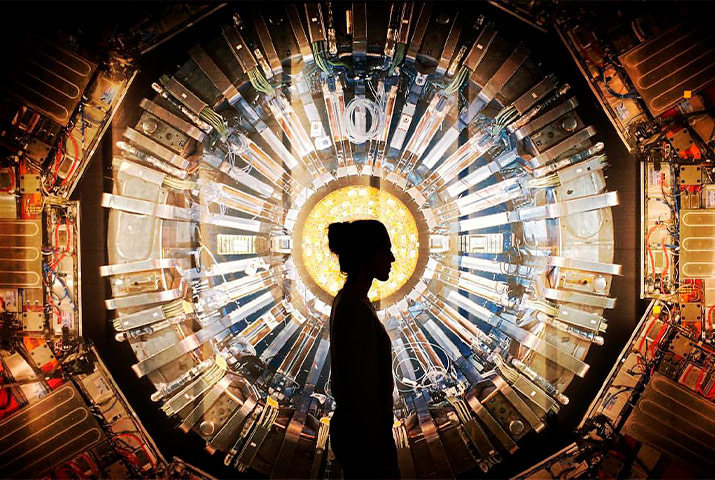

Silhouette at Large Hadron Collider | CC BY-ND Har Gobind Singh Khalsa Seguir

The skeleton of a building with a glassless dome is all that remains of the old Hiroshima that was destroyed by the atom bomb. If you walk along the paths that circle the A-Dome and look through its empty windows and the holes in the walls, on the other side there’s nothing to see: only blue sky and emptiness. Nowadays, beyond the memorial area, skyscrapers comprise a modern city not much different from other Japanese cities. But this testament remains, and each year paper cranes are placed to remind us of what befell humanity on 6 August 1945.

The atom bomb that brought an end to one war and started another would not have been possible without quantum mechanics. And quantum mechanics was a turning point in the world of physics, because it allowed us to see what had never been seen before: the fundamental particle which matter is made of.

In truth, the quantum age had begun back in 1900, when the German physicist and mathematician Max Planck formulated the first quantum theory, according to which certain magnitudes, such as energy, cannot be based on arbitrary values, but rather on so-called “quantum” units. Even light, which appears to be a continuous beam, is made up of these quantums, the fundamental particles called “photons”. This discovery was a turning point in the world of physics, but it was the dropping of the atomic bombs Little Boy on Hiroshima and Fat Man on Nagasaki, three days later on 9 August 1945, that made clear just how far science had advanced and the immense power of a tiny particle.

The two atomic bombs were developed through a research project led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada. The Manhattan project, which ran between 1939 and 1946, was led by the nuclear physicist Robert Oppenheimer. Among the experts that worked with him was the Danish physicist Niels Bohr, who in 1913 had speculated that the atom is like a solar system with a nucleus at the centre and a cloud of electrons around it. In 1941, Bohr was visited in Copenhagen by Werner Heisenberg, a former student who at the time was responsible for a project to develop Hitler’s atom bomb. Heisenberg put his life at risk to explain the German project to Bohr, in the hope of stopping it. Heisenberg and other members of the team were recruited under The Alsos Mission, a counterintelligence operation to stop the Nazis making the bomb. Hitler never did get his nuclear weapon.

Quantum mechanics and secret projects to build nuclear bombs will be one of the themes of the next edition of Kosmopolis. K19 will attempt to explain how, from literature to science, quantum physics influences our concept of reality.

K19 will stage a dramatized reading of Copenhagen, a play by Michael Frayn, written and first performed in 1998, that tells of the meeting between Bohr and Heisenberg that possibly changed the course of history. We’ll also see

That’s the story!, a documentary by José Ignacio Latorre, Professor of Theoretical Physics at the UB, and Maite Soto, Audiovisual Communication and Advertising Lecturer at the UAB. The film tells the story of the Manhattan project and includes an account from the sole surviving participant, the physicist Roy J. Glauber, together with never before seen images, declassified shortly before 2015.

Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr, 1934 | Wikipedia | Public Domain

A new start

Someone who knows this story well is the science writer Philip Ball, author of Serving the Reich. The struggle for the soul of physics under Hitler and Beyond weird: why everything you thought you knew about quantum physics is different. Ball will talk to José Ignacio Latorre about this nuclear arms race, but he will also discuss what may be the next technological revolution: the quantum computer. If the discovery of nuclear fission marked a turning point in the balance of the world powers, the development of so-called quantum biomimicry may come to mean another full stop: last October, a quantum computer managed to create a system that can learn, memorise, interact and copy itself, mutate and die. In other words, the building blocks of artificial life have been virtually created. Where will this discovery take us? Will it be the start of a new quantum era?

To round off this scientific line up, we will also be joined by Lisa Randall, an expert in particle physics and cosmology and one of the most prolific science writers working today. And there is a certain cosmic justice in the fact that a female scientist should bring the tenth biennial edition of Kosmopolis to a close, given that in the times of Planck, Bohr, Heisenberg and Glauber, quantum physics was a man’s game.

But Kosmopolis is an amplified literature festival, so apart from the more scientific side, there will also be room for narrative and series from old friends of the festival: Sònia Fernández Vidal, who took part in K13, and Víctor Sala, one of the members of Serielizados, who joined us for K15 and K17. The two of them, together with the philosopher and critic Joan Burdeus, will discuss series and quantum physics as well as scriptwriters’ fascination with physics, and they will explain why, for example, Walter White’s alter ego is called Heisenberg.

Once again science and literature are brought together at Kosmopolis, where we continue to defend the idea of a third culture in which these two disciplines are not antagonists but protagonists of the same story.