On W.G. Sebald’s Radicalism

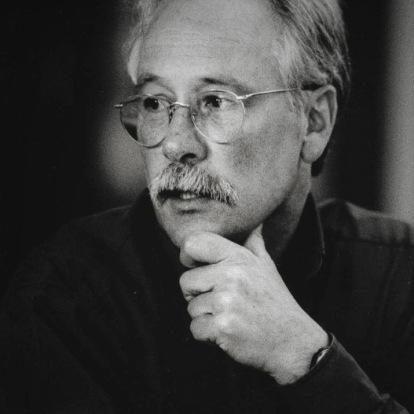

13 .04 .2015 - Uwe Schütte

Uwe Schütte met W.G. Sebald in 1992 when he arrived at the University of East Anglia as an MA student, eventually becoming Sebald’s doctoral student. He has published a number of articles and books on Sebald’s wide-ranging body of work . Schütte’s latest publication, the first in-depth study on his former adviser’s critical writings appeared in November 2014, is entitled Interventionen. Literaturkritik als Widerspruch bei W.G. Sebald. In this essay he examines the idiosyncratic radicalism underwriting Sebald’s views on German politics, post-war society and the academic discipline of German Studies.

W.G. Sebald / Nuvol; SEBALDIANA

Winfried Georg Sebald, born in 1944, belonged to a radical generation known as the “1968ers” in Germany, who were the first who had no direct experience with the war. From the mid Sixties onwards, the atrocities committed by the Nazis could no longer be ignored, as younger Germans began asking pointed questions to a decidedly conservative post-war society. Quite naturally, they fiercely questioned their parents’ involvement with and complicity in National Socialism. This interrogation was not limited to the domestic sphere either—teachers, judges, politicians, and university professors all came under scrutiny for their conduct during the Nazi years.

The Auschwitz trials from 1963 to 1968 were a crucial turning point for this generation. Sebald, who was studying German and English literature at the University of Freiburg, would later explain that the trials were “the first public acknowledgement that there was such a thing as an unresolved German past. I read the newspaper reports every day and they suddenly shifted my vision. And I understood that I had to find my own way through that maze of the German past and not be guided by those in teaching positions at that time.”

And this was exactly what he did. First, he left Germany to study abroad – in Francophone Switzerland at the Université de Fribourg, and then followed by a short stint in Manchester. Second, he sought intellectual guidance from a number of Jewish intellectuals associated the Frankfurt School, in particular Walter Benjamin and Theodor Adorno. Third, he never let go of his suspicion that all leading professors in German Studies were former Nazis. He reserved his deepest resentment for those who suddenly transformed themselves in messianic boosters for specific authors—something that reeked of self-serving to Sebald. Despite the dangers of this wholesale mistrust, he was often right.

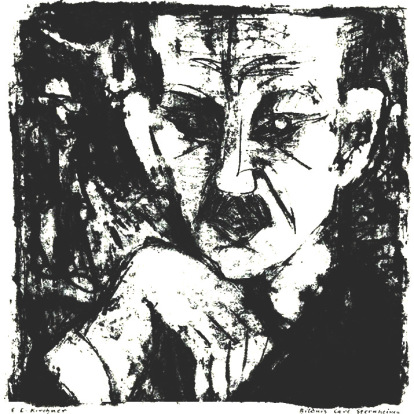

Portrait of Carl Sternheim. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner / [PD]

His first book on the German-Jewish playwright Carl Sternheim is a good example. Published in 1969, it began as his master’s dissertation on Sternheim, who had enjoyed considerable success during the late nineteenth century but had largely faded away from the Germanic literary sphere. Thanks to a campaign led by Professor Wilhelm Emrich, Sternheim’s plays experienced a widespread revival on the stages of post-war Germany. Sebald’s study on Sternheim was both a vicious attack on the dramatist, whom he exaggeratingly accused of being a proto-Nazi, and an attack on Emrich, whom the young critic accused of a turning a blind eye to what he saw as Sternheim’s many literary and moral failings.

Not surprisingly, this very polemical book was met with substantial criticism. “Everything that Sebald writes is sheer nonsense”, snapped one reviewer, who himself suspected that Sebald might be a neo-Nazi due to his attack on a playwright with Jewish roots. The reviewer should have, however, taken Sebald more seriously, as it would later come out that the widely-respected professor at the Free University of Berlin had followed an all too German career trajectory. Originally a member of the communist student organisation, Emrich joined the Nazi Party in 1935 and served dutifully in various high-ranking positions, including a stint in Goebbel’s Ministry for Propaganda. After the war, he quickly turned into a fervent democrat—and never brought up the unseemly details of his past again.

Sebald’s critical writings are in many ways an obvious form of student rebellion against the (academic) establishment. By attacking the very group of people among whom he also longed to be counted, we can see a character trait that later manifested in his literary writing: a pronounced desire to know and speak the truth. His mistrust of authority, both academic and literary, never went away. In the Nineties, he wrote a scathing polemic against the writer Alfred Andersch, another redeemed figurehead of post-war German literature. Sebald had always found his texts lacking in aesthetic merits, and when a monumental biography of Andersch was published in 1990, he realized why.

As the Nazi death machine was launching into overdrive, Andersch divorced his Jewish wife in order to be able to publish. His ex-wife survived the war, by which time Andersch had become erotically entangled with an artist with excellent connections to the Nazi party. Later, as an American POW, he exploited his former marriage “to a mongrel of Jewish descent” to have confiscated papers returned to him. Such blatant opportunism as well as the unacknowledged guilt that Andersch evidently felt later about his shameful behaviour was, according to Sebald, responsible for the aesthetic malaise that mars his novels. Once again, Sebald’s sweeping dismissal of Andersch’s writings was initially fiercely opposed. Over the last two decades, however, new pieces of evidence have emerged, vindicating Sebald’s dogmatic belief that a morally compromised author cannot produce aesthetically valid literature.

Norwich Train Station / SEBALDIANA [cc]

Sebald’s decision to leave the German academy in order to escape its paternalistic system dominated by politically compromised professors proved successful. Both in Manchester and at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, where he began teaching in 1970, he worked at politically progressive institutions. Initially, it seemed to him that he had finally found intellectual refuge in Britain, but this feeling did not last very long: “Conditions in British universities were absolutely ideal in the Sixties and Seventies. Then the so-called reforms began and life became extremely unpleasant”, Sebald explained in 1996. “I was looking for a way to re-establish myself in a different form simply as a counterweight to the daily bother in the institution.”

It was first and foremost the increasing frustration that Sebald felt about the deteriorating working conditions at British universities that led him to take up literary writing. In personal conversations he was very vocal in his condemnation of neoliberal education policies and the bureaucrats in his institution who implemented them. As a philologist, Sebald particularly detested the spread of management-speak, whereby the academy was redefined as a part of the “knowledge industry”. Angry cursing and comparisons to “Stalinism” abounded when he expressed his disgust to me about the imposition of profit-driven, short-term policies aimed at making universities into businesses and redefining students as client, both of which had the effect of curbing academic freedom.

In a brave act of professional disobedience that had serious repercussions for him professionally, he once ejected government-mandated assessors out of his classroom as part of a “quality assurance” exercise. Although in Austerlitz, the title character explains his decision to resign from academia due to “the inexorable spread of ignorance, even to the universities,” Sebald himself shied away from making such a bold move. Instead, he tried to balance his two careers, academic and literary, despite the considerable toll it took on his mental and physical health.

Another factor motivating him to write literary texts was his almost blanket rejection of German post-war literature. He chose to explore largely ignored areas corners of the Germanic literary canon, including stories of the Jewish emigrants, the afterlife of guilt of those who survived fascist persecution, the inability of the victims of Allied air raids to speak about their traumas, the notion of literary writing as a form of auto-destruction and, last but not least, the fateful ties that connect human history with natural history.

Sebald’s intellectual radicalism certainly did not wane. Right until the end of his life, he never shied away from expressing thoughts that broke the rules of professional politesse. Questioning the German dogma of the uniqueness of the holocaust in his last German interview is one very pertinent example. Connecting a postcard depicting a pile of herring at Lowestoft fish market with a photograph of bodies of (presumably) dead Jews in the third chapter of The Rings of Saturn caused similar consternation amongst a number of German critics.

Likewise, some were offended by his avowedly anti-clerical stance towards the Catholic Church, while others worried about his provocative thesis that the “strikingly stunted growth of the population” as well as the remarkable frequency of “hunchbacks and lunatics” in Belgium is related to the crimes of the colonial past. (Clearly a nod to Thomas Bernhard who similarly connected collective crimes with physical deformities of individuals.)

Air war and literature (German edition) / SEBALDIANA

At the very core of Sebald’s melancholic Weltanschauung [worldview] is the fundamentally bleak insight that destruction – and not creation – is the organising principle of nature. Like Gnostics, he viewed the world as a process of decay, and he saw humanity as a helpless subject of the destructive machinations that govern human history. Wars, atrocities, and genocides of all kind are not exceptions but symptoms and indicators of an all-embracing ‘Natural History of Destruction’ that crushes human aspirations in the name of a secure future, to create a better society or to build a world without war and misery.

Sebald uncompromisingly regarded “our insane presence / on the surface of the earth”, as he put in his prose poem Nach der Natur (After Nature), as the hallmark of an aberrant species trying to make sense of a natural world whose “regeneration is proceeding / in downward orbits”. It amounts to no less than a radical dissent from all political ideologies, religious beliefs, philosophical systems and academic theories that promise progress and personal happiness. Later, when his outlook on life darkened further, he came to believe that the (seemingly autonomous) realm of art was also affected by the destructive tendencies at work in our world. But rather than to give in to nihilism, he carried on with his writing – until the tragic, premature end of his life.

Uwe Schütte is a Reader in German at Aston University, where he has taught since 1999. He has a PhD from the University of East Anglia, where he studied under W.G. Sebald. Figurationen, his new book about Sebald´s poetry has just been published by Edition Isele in Eggingen, Germany.