THE SEBALD MYSTERY

05 .05 .2015 - Cynthia Rimsky

Once, in Valparaiso, I thought I had discovered the key to Sebald’s writing in a book by him I had borrowed. Over the years, I forgot the title and the sentence. Now that I am borrowing, at random, another book by him, I wonder what those few lines were: lines that seemed so crucial to me ten years ago.

[Translated by Mark Waudby]

Film frame ‘Again’ I (2004), Andrea Goic [cc]

During my perambulations, I got to know, or knew by sight, the locals I hoped I would recognize 15 years later when I was already living and working in Santiago. Until the day came when not a single gesture remained and I read in the newspaper that the nougat vendor has passed away. “There was a nougat vendor in Valparaiso, but he died and nobody in his family continued with the business. None of my three children or six grandchildren wanted to follow in my footsteps. I tried to entice them, like my grandparents did with me, but none of them liked it. Today they all prefer computers”.

After revisiting Valparaiso, I returned there often. My friends married, they had children and I no longer stayed with them. This time I lodged in a borrowed apartment in one of the new buildings that are destroying the hillsides, and in the library I found a book by Sebald I didn’t know. I don’t remember the date, or the title, but I do remember the thrill of discovering a few short lines in which he revealed what his writing was made of. Why didn’t I steal the book, write down the title or the sentence? For the very same reason I didn’t stop to speak to the nougat vendor to ask him how he made his nougat, or didn’t jot down my observations in a notebook so I could write them up when he was no longer there.

- Kohler Medicinal Plants, 1887 [PD]

Three years ago, I crossed the Andes by bus with just a couple of suitcases. I was bound for Buenos Aires, where I currently live as an emigrant. I kept my books in Santiago, except for the ones that fitted in the suitcase. In addition to the two by Sebald, there were two that belonged to my partner and one we had bought between us. Now that I have been asked to write this text, the mystery revealed to me in Valparaiso goes round and round in my head and, because there isn’t time to sift through all the books, I pick one out at random and I read: “In Vienna, I would set out and walk without aim or purpose through the streets of the inner city”. It sprang to mind that the book may have been Vertigo; and this may have been the sentence; and, the mystery, the fact that Sebald cultivates images as if they were plants in his garden.

For instance, in the first story, Beyle, or Love is a Madness Most Discreet, he says: “… Beyle drew Mme Gherardi’s attention to an old boat, its mainmast fractured two-thirds of the way up, its buff-coloured sails hanging in the folds. It appeared to have made fast only a short time ago, and two men in dark silver-buttoned tunics were at that moment carrying a bier ashore on which, under a large, frayed, flower-patterned silk cloth, lay what was evidently a human form…” This image could be the result of Sebald grafting on a scene from Kafka’s Hunter Gracchus, where a hunter who dies after pursuing a chamois in the Black Forest is condemned to roam the seas eternally on a boat without a helm.

The technique allows both of them – scion and rootstock – to join together like a plant and coexist. The only requisite: they must belong to the same family, thereby guaranteeing functional compatibility, the interaction of cells and the flow of vital substances. In Dreams, Walter Benjamin describes a familiar experience. While visiting the house of the O family in Dutch India, he enters a room panelled in dark wood that gives a feeling of opulence. His guide tell him there’s more and invites him to climb a staircase. When he looks down, “before my eyes there spread before me that warm and nostalgic wood-panelled room that I had left but a moment ago”. According to Benjamin the familiar takes place when you’re making a journey for the second time. Sebald was able to write Vertigo after repeating the journey he was forced to curtail years earlier. And that first time, in Riga, he had retraced Kafka’s steps.

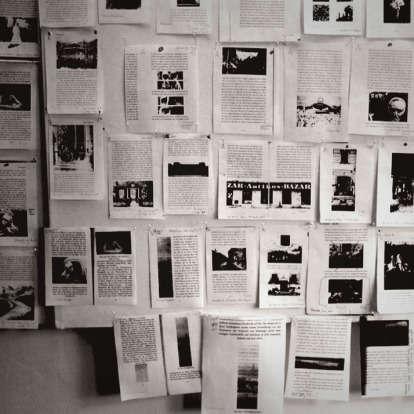

Pictures from Sebald´s books, Cultural Inquiry [cc].

- Pages with pictures of the work of Sebald, Cultural Inquiry [cc].

In order to make a graft you need a very sharp knife that will make a clean incision. In this way, Sebald cuts away from Kafka’s story the golden buttons, the boat, the flower-patterned cloth, the two young men he meets on the bus, the dice, the quayside, the doves, the boatmen, the canal, when he wakes up in the hotel and feels as if he has just been plying a vast ocean… He doesn’t only cut out images from The Hunter; throughout the book he grafts on other characters, places, ideas and stories from other writers.

For a graft to take, the cambia of the scion and the rootstock must come into contact. The cambium is a very fine green-coloured layer of cells (less than 1 millimetre), over the white layer – before the page –, that produces the cells that will form the vascular tissues – which the water and sap with their nutrients flow through – and makes the graft weld. Sebald brings into contact the shadows present in both images. Thus the image of the boat is cast, like a shadow, on Madame Gherardi; and Ludwig of Bavaria, Dante, Casanova, Kafka himself, Stendhal, the sacristan from the Pellegrini chapel, the war, destruction…appear.

Just as a plant has to be tied with a piece of twine so it won’t be affected by dryness, wind or any other movement, Sebald uses coincidences to keep the graft in place. It doesn’t matter that he buffets them with his anguish, weightlessness, circles, melancholy or fear, the coincidences fix the image in the story he is telling and, in spite of all their movements for and against, they don’t become detached.

Vertigo may well be the book and “the days not taken up by my customary routine of writing and gardening tasks” the sentence I discovered in Valparaiso, but something makes me doubt this. I had the idea of looking on the internet to find out if the names of the places and people he encounters on his travels really exist. Ernst Herbeck was locked up in a psychiatric hospital “tormented by the insignificance of his thoughts” until a new doctor handed him a pencil and paper. His poems are still published today. Greifenstein Castle is on sale for 2 million 800 thousand euros. Kritzendorf is constantly being flooded. The miners in Schneeberg are dying of lung cancer. Ludwig II of Bavaria “was a sick soul with a troubled and melancholy spirit, engrossed in the deliria of his soul”… I look up Grillparzer, who Sebald remembers in Venice, and I find that the core theme of his output is “the individual, divided between his inner ego and the outside world, who doesn’t find a possible reconciliation for these opposites”.

I don’t remember how far I delved that night to find what was real about his writing. The moment came when I understood that Sebald didn’t go on these journeys or if he did, they didn’t happen as he describes them. Perhaps the only thing he needed was to go into his garden to tend his plants. What I do remember is that a few hours earlier when a friend of mine read my I Ching, the Opposition hexagram came up. When I awoke I found that the book was open at page 88 and, underlined in shaky graphite pencil, the words that had revealed to me, in Valparaiso, the mystery of how Sebald’s books were made and how the old guy, who used to stop outside the Condell Cinema, made his nougat with fire and marble.

Now that Chile has ceased to be a return and become a round trip that has me immersed in the Opposition, I read once again the sentence which, 15 years ago, I believed held the answer to the mystery of my life ahead. “I sat at a table near the open terrace door, my papers and notes spread out around me, drawing connections between events that lay far apart but which seemed to me to be of the same order.”

Cynthia Rimsky, Santiago de Chile, 1962, currently lives in Buenos Aires. She has written the books Poste restante (2001 and 2010), La novela de otro (2004), Los Perplejos (2009), Ramal (2011) and the text Cielos Vacíos in the anthology Nicaragua al cubo (2014). Her writing takes place on the border of genres. Rather than novels, she builds journeys made by characters who are remote both in the imagination and in reality, who don’t seek to get anywhere but “to find a rarefied angle from which to see themselves”. Her writing project is shaped by detailed observations, the inclusion of images, maps, photos, the description of a long-term experience of rootlessness, writing and accident as inevitable. She currently teaches courses and workshops about flâneurs, travel writing and literary reviews. She is a regular contributor to the media.