Sebald: the rings of the journey and death.

06 .07 .2015 - Jorge Carrión

To conclude this series of articles, Jorge Carrión, the writer and curator of the exhibition Sebald Variations –to which this blog is a companion piece – retraces the steps of the German author to weave together a canvas of the spaces and worlds that shaped Sebald’s universe. We travel alongside Carrión and Sebald – it could not have been otherwise – through landscapes, cities, bookshops, railway stations, characters, writers and countless literary echoes. ‘Because our obligation is to be witnesses, although we don’t know exactly what to…’

Article published in the magazine Cultura / s of La Vanguardia. Barcelona 07/03/2015.

![L'oeil oder die Weisse Zeit [1]](https://kosmopolis.cccb.org/wp-content/uploads/Retrato1_JanPeterTripp-414x414.png)

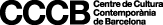

L’oeil oder die Weisse Zeit [1]. Jan Peter Trip (2003).

In June and July 2003, when I was psyching myself up for a long trip through America, which, deep down, I was afraid of embarking on, I tried to combat my fear by following Sebald’s footsteps through Europe. With this purpose in mind, I spent a few days in London and Paris, the two main metropolises in Austerlitz. The solid, ultra-modern Napoleonic architecture of the Bibliothèque Nationale was in stark contrast to the lightness of the Pont Mirabeau, where Apollinaire and Celan committed suicide. I also retraced the wanderings of the Sebaldesque characters through the Gare d’Austerlitz and Liverpool Street Station, because the future of Jacques Austerlitz – one of the hundreds of children sent to England to save their lives – lies in the atrocious flow of energy that connects both stations. I didn’t see the monument erected in 2006 commemorating the Kindertransport until I returned to London years later. Sebald’s novel, therefore, anticipated politics and carried out its own symbolic reparations.

Because it is our obligation to be witnesses, although we don’t known exactly what to, on another journey I witnessed other works that erased other traces. The builders and painters who were refurbishing the former offices of the British Centre for Literary Translation at the University of East Anglia, in Norwich, were unaware that Sebald had spent his entire adult life within their walls that no longer existed. Only the trees survived, on the other side of large windows, bathed in a diffused, almost underwater light. While the hammers rained down, the lecturers at the institute founded by the author of Pútrida patria (Anagrama, 2005) – with the purpose of giving students an in-depth knowledge of international literature – prepared their classes in the library or cafeteria. There had been no professor of literature at East Anglia since 2001. In fact, as the years went by, the presence of literature not written in English on the university syllabus began to fade. ‘L’oeil oder die Weisse Zeit’(2003), a multiple portrait by the painter Jan Peter Tripp shows Sebald’s ‘Acceptance Speech to the Collegium of the German Language’ (Campo Santo, Penguin, 2006). During his address, Sebald says that his homeland always seemed “unreal” to him, “like an endless déjà vu” and that in England he always hovered between “feelings of familiarity and dislocation”. His life was a tense translation.

![L'oeil oder die Weisse Zeit [2]. Jan Peter Trip (2003).](https://kosmopolis.cccb.org/wp-content/uploads/Retrato3_JanPeterTripp-414x414.png)

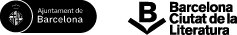

L’oeil oder die Weisse Zeit [2]. Jan Peter Trip (2003).

Quality, ambition and perseverance are words that are unpredictable in meaning, but they certainly highlight the parameters within which writing that leads to enduring readings moves. Fifteen years after Austerlitz was published, judging by his face in English, American and German bookshops, Sebald has established a reputation as a minority writer, the subject of doctoral theses and academic conferences but also as an author who is read with painstaking attention to detail by demanding readers, who are prepared to spend a small fortune to buy a book abroad, to learn a language to understand a book that hasn’t been translated, to travel in order to tirelessly browse through bookshops, to descend to the catacombs of libraries and dictionaries and search engines in order to better understand a text. Like Robert Walser, Vila-Matas and Roberto Bolaño, who are also extraterritorial writers, Sebald has also left his mark on other types of reader who are neither academics or scholars; the people who make reading not only into a journey but into contemporary art too: film directors such as Grant Gee, multifaceted writers like Iain Sinclair and Teju Cole and artists includingDominique González-Foerster, Tacita Dean, Jan Peter Tripp, Carlos Amorales oand Jeremy Wood. , have followed in his footsteps. This blind faith in tenacious readers and the readings that eventually come, allows us to move forwards, albeit sinking into the liquid darkness, to nowhere.

L’oeil oder die Weisse Zeit [3]. Jan Peter Trip (2003).

“For a long time no one could account for this glowing of the lifeless herring, and indeed I believe that it still remains unexplained”, we read in The Rings of Saturn, Sebald’s book of travels through this region of eastern England and his most influential work among other writers and artists. In the opening pages of the book he mentions the death of two of his colleagues from this faculty that was open to European languages: Michael Parkinson and Janine Rosalind Darkyns; and to one of his neighbours, Frederick Farrar. The book was published in 1995 and six years later its author died in a car accident. Another of the real-life characters in the book, Michael Hamburger, also died shortly afterwards. Like Borges, Thomas Browne, Conrad, Casement, Chateaubriand and the remaining ghosts who wander the pages of these essays and travelogues that could also be entitled The Book of the Dead.

I went to Saint Andrew’s church in Framingham, in search of Farrar’s grave, which I thought would be near Sebald’s. In the middle of fields and woods and isolated houses, the stone basilica had no more than a hundred tombs around it. I read the names of the deceased. One. By. One. There was no trace of Farrar. Or of the person who immortalised him. After walking for a second time around this ring of the dead, I asked one of the gardeners if there wasn’t another Saint Andrew’s church in Framingham apart from this one. “That’s correct”, he replied, reminding me that I was in Framingham Pigeon and just over a mile away there was Framingham Earl with its Saint Andrew’s church. A triangular road sign reminded me that I had to watch out for the ducks crossing the road.

![L'oeil oder die Weisse Zeit [4].](https://kosmopolis.cccb.org/wp-content/uploads/Retrato2_JanPeterTripp-414x414.png)

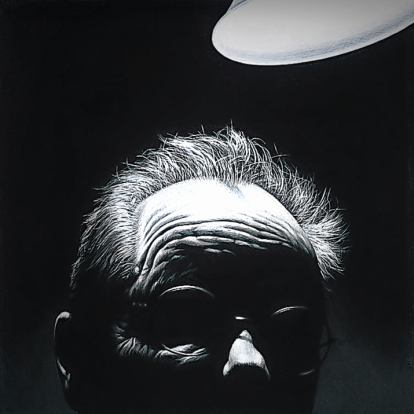

L’oeil oder die Weisse Zeit [4]. Jan Peter Trip (2003).

Jorge Carrión holds a PhD in Humanities from Pompeu Fabra University, where he teaches contemporary literature and creative writing. He has published the essays Teleshakespeare (Errata Naturae, 2011) and Viaje contra espacio. Juan Goytisolo y W.G. Sebald (Iberoamericana, 2009); the travel books Australia. Un viaje (Berenice, 2008), La piel de La Boca (Libros del Zorzal, 2008), GR-83 (Autoedición, 2007) and La brújula (Berenice, 2006); and the novels Los muertos; Los huérfanos and Los turistas (Galaxia Gutemberg 2014/2015). He curated the exhibition ‘Sebald Variations’ together with Pablo Helguera.