Five “crucial events” in the Life of W. G. Sebald

23 .02 .2015 - Mark M. Anderson

W.G. Sebald’s life and work confront every biographer with the deliberate fictionalization of everyday events in the author’s biography—a constant theme in his postmodernist, semi-documentary and autobiographical writing. Five key events from his inner as well as outer lives are described, ranging from the bombing of Germany at his birth to his relationships with his father and maternal grandfather and finally to his emigration and a key biographical event for the beginning of his writing.

“. . . for in reality, as we know, everything is always quite different” W.G. Sebald. Vertigo.

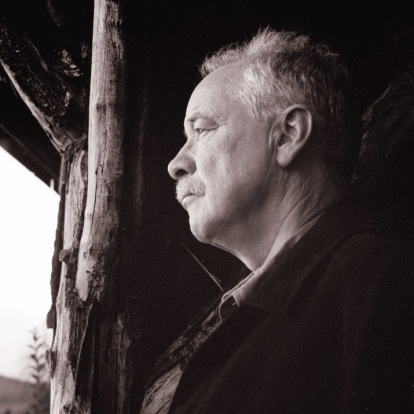

W.G. Sebald portrait / Jan Peter Tripp

Every aspiring biographer of W. G. Sebald is confronted with the fictionalization that Sebald the author performed on the life of Sebald the narrator/character who appears in his literary works. Dates of birth, death, employment, book publication and the like are certainly momentous in the empirical life of W. G. Sebald, but not in that inner, subjective biography which is undoubtedly more interesting to his readers. But how to distinguish between biographical fact and invention? Sebald himself deliberately made such a distinction difficult if not impossible—his narrators seem to reflect his actual life as a professor/writer born in Germany and living in England, but the books make no reference, for example, to his family life with a wife and daughter. Sebald the narrator is always alone, the quintessential outsider and wanderer; Sebald the author less so. What follows is a list of five important events in W.G. Sebald’s life, starting with an event that occurs before he is even born. The first three events are squarely from the realm of the Sebaldian narrator’s partially invented, inner biography. The last two–from a much later point in his life–have a historical validity that pertains to his own generational position in postwar Germany.

1) The Air War on Germany

On the night of 28 August 1943, 528 Allied planes bomb the city of Nuremberg. Rose Sebald, née Egelhofer, is returning home from a visit to her husband in Bamberg, then an officer in the Wehrmacht. She gets as far as Fürth from where she sees Nuremberg in flames; shortly thereafter she notices she is pregnant. Born eight months later on May 18, 1944, Sebald grew up in his mother’s village at the foot of the Alps in southwestern Bavaria, near the Austrian and Swiss borders. The bucolic site was never bombed and so Sebald grew up without any concept of destruction. But for the narrator of After Nature, the moment when Rose Sebald turns back to look at the destruction of the center of the Nazi Party rallies establishes his own direct link to this nearly biblical destruction, “as if I had already seen it all before.” The bombing of Germany will haunt his adult life and virtually all of his fiction. Ironically enough, Sebald lived for almost thirty years on the northeast coast of England, a short distance from where the English planes began their war-time sorties over Germany.

2) Foerign Fathers

![Wertach Soldier monument / SEBALDIANA [cc] Wertach_](https://kosmopolis.cccb.org/wp-content/uploads/Wertach_-414x414.jpg)

Wertach Soldier monument / SEBALDIANA [cc]

3) The Natural Philosopher

Sebald’s “true” or chosen father was his grandfather Josef Egelhofer, who had served as village constable in Wertach from the early part of the 20th century until his retirement in the 1930s. By all accounts a sensitive, gentle, humorous man, he never received much formal education. But he was intelligent and curious, particularly about the physical world around him. Gertrud Sebald calls him a “Naturphilosoph” or “natural philosopher”. The retired Egelhofer, whose profession had required him to patrol the surrounding region on foot, took his grandson on long walks, teaching him about mountain flowers and herbs, meteorology, geology, but also about the village residents whose life stories he knew so well. He is Sebald’s first and most beloved mentor, a role that was strengthened by the absence of his son-in-law Georg, who worked in a neighboring town and returned home only on weekends until 1952. Egelhofer died in April 1956, on the night of a great snowstorm, a few months before his grandson finished elementary school. His death will leave perhaps the largest imprint of any single event in Sebald’s inner landscape. His first novel, written during his university studies but never published, turns on the long description of the grandfather’s funeral and burial. But Egelhofer’s presence can be felt in the published works as well: in the reverential bond between the young narrators in The Emigrants and Austerlitz, and an older, wiser, male mentor figure such as Henry Selwyn, Max Faber, Jaques Austerlitz—victims and melancholy survivors of a much earlier personal catastrophe.

4) A Life Abroad

W.G. Sebalds’s hand / Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach

The move from Freiburg (in Germany) to Fribourg (in Switzerland) in October 1965 marks the momentous if unwitting break with Germany and the beginning of his emigration, first in Switzerland and then in England, where he will live until his death in 2001. It didn’t start as a deliberate plan to emigrate—the move to Fribourg was prompted by his desire to escape the stuffy, morally compromised environment of the German faculty members at Freiburg University, where he had initially studied. It also gave him the chance to study rent-free, without his father’s financial support, while living in an apartment with his beloved older sister Gertrud and her Swiss husband, Jean-Paul Aebischer. During his stay in Fribourg, Sebald completes his Masters degree with distinction in nine months in French (a language he had hardly studied beforehand), working with a Viennese professor who had opposed the Nazis and emigrated to Switzerland before the war. Here begins Sebald’s connection to victims and exiles of the Nazis, which continues in important relationships in England, where so many persecuted German Jews had found refuge. Just as importantly, the stay in Fribourg will teach him what life in a foreign country and language can offer in the way of inner freedom and relief from his generation’s burden of Germany’s war crimes—a burden made simultaneously more self-conscious and lighter by living among non-Germans. Emigration was part of the family DNA. All three of Sebald’s maternal aunts and uncles emigrated from Germany in the 1920s to the United States and remained there until their deaths; Sebald’s own two sisters, Gertrud and Beate, moved to Switzerland early in their lives and reside there today. But emigration was also part of his generational heritage as a child born during or just after the war, the generation that will come of age during the 1960s and, quite often, seek their fortunes abroad.

5) Where it all began

In the winter of 1983, while living in Norwich, England, Sebald received news from his mother of the suicide of a beloved elementary school teacher named Armin Müller. Rose sent him newspaper clippings reporting the gruesome death—the retired teacher had lain down on the railroad tracks just outside Sonthofen—and through them Sebald discovered that Müller, much to his surprise, had been a victim of the Nazis during the 1930s. As a quarter Jew he was barred from teaching German children early in the Nazi regime (though, paradoxically, he would be drafted by the Wehrmacht in 1939 as a three quarters German and would serve the Fatherland for six years). Sebald’s discovery of yet another example of the conspiracy of silence perpetrated by parents and teachers about the town’s true involvement in National Socialist persecution engenders in him contradictory emotions: fury at being lied to as a child by familiar authority figures, but also guilty mourning for a beloved teacher whose true identity and past persecution, he suddenly realizes, he had never properly understood. The mixed emotions are a potent catalyst for his literary work and lead him to write the story Paul Bereyter in The Emigrants. One of his most moving stories, it establishes the model for the semi-documentary, ethically engaged fiction that will become his literary signature.

Mark M. Anderson is the author of several books on Kafka (Kafka’s Clothes, Reading Kafka), and editor and translator of contemporary Austrian writers such as Ingeborg Bachmann and Thomas Bernhard. His work focuses on the German modernism, contemporary Austrian literature and theory and practice of translation. Regularly offers courses on modern German-Jewish culture from 1750 to the present; and the idea of music in German culture and German exile during the Nazi period. In comparative literature has worked on very diverse topics as “Problems of Gothic”, “The materiality of the book in Western Culture” and “Jewish Identity in Modern European Culture” at Columbia University.