The clocks of Austerlitz (I)

16 .03 .2015 - Graciela Speranza

Two clocks mark our first encounter with Jacques Austerlitz, the protagonist of W.G. Sebald’s final novel which was launched into the new millennium in 2001 like a sombre coda to the history of the 21st century and a profession of faith in the art of the 21st century. A narrator, who is hard to distinguish from Sebald himself, approaches Austerlitz in Antwerp Centraal Station, intrigued by one of the few travellers who isn’t staring apathetically into space in the Salle des pas perdus, but paying close attention to the station’s monumental architecture while making sketches, notes and taking photographs.

[First of two parts] [Translated by Mark Waudby]

Clock parts / martinak15 / SEBALDIANA/ Foter / CC BY

This is the start of a long conversation that continues into the early hours in the station buffet and continues during more than 20 years of chance encounters, described in a single, sinuous paragraph of almost 300 pages, punctuated by the occasional photo that engages in an oblique dialogue with the story. We gradually find out that Austerlitz’s research into 19th century architecture, which dominates the conversation during their first encounters, is just a veil that delays a more painful investigation into his true origins that will be revealed in other conversations. Brought up in Wales as Dafydd Elias by a Methodist minister, Jacques Austerlitz is really the son of a Jewish family from Prague who was sent to England on a Kindertransport in 1939, shortly after his father had tried, in vain, to make a life for himself in Paris where all traces of him were lost, and before the Nazis deported his mother to the Terezín concentration camp, where she was held before her death in the gas chamber in 1944. Summarised thus, Austerlitz could be seen as the crowning achievement of the narratives of a generation of Central European writers who embraced the recovery of the German historic memory by exorcising the traumatic legacy of the holocaust in fiction. However, no plot summary could attempt to describe the subtler story that interweaves the 88 images that punctuate the text. The images appear to document the story with the undeniable truth of photos, yet they divert, dealign and place it off centre with no aesthetic pretensions. More akin to Alexander Kluge’s formal experiments and Bertolt Brecht’s theatrical productions, Austerlitz doesn’t allow itself to be reduced to the linear causality of the plot or to the cultural shortcuts of the critique that binds Sebald’s works to the traumas of German history, post-memory and modern melancholy. The story is imbued with the power of the image and disrupts the linearity of reading with the unexpected explosion of detail which, in the toing and froing between what is said and what is seen, triggers other stories. Other stories could be written in light of this flow of clues between images and texts which, like arrows, hit the target that is the Other. A story about clocks, for instance.

Amberes Central Station / Kimb0lene / Foter / CC BY-NC-ND & SEBALDIANA

There are no photos of clocks in the first few pages of Austerlitz, yet they dominate the scene in Antwerp Centraal Station that opens the novel, like the punctum of the first encounter with Jacques Austerlitz. The chance conversation in the Salle des pas perdus continues in the station buffet and time passes, guarded by a mighty clock under the lion crest of the kingdom of Belgium, the dominant feature of the semi-deserted restaurant in the early hours of the morning. While Austerlitz talks about the colossal scale of the station, and how it was built in the late 19th century like a profane cathedral consecrated to international trade and the boundless optimism of a small country that believed in the inexorable progress of its expansion as a colonial power throughout Africa, the pauses in the conversation become endless, regulated by the predictable movement of the six-foot-long hand of the clock which “resembled a sword of justice” and sliced off the next one-sixtieth of an hour from the future “with such a menacing quiver” that one’s heart almost stopped every time it jerked forward. It is the first clock in a series which, according to the “historical metaphysic” Austerlitz reads into the monumental ambition and extreme rationalism of modern architecture, leads, a century later, to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. However, the true nature of the time of the clocks that control, compress and commodify the time of life, their cogs hidden away inside the machinery of imperial expansion and capital accumulation, is revealed more forcefully by the giant clock in the station foyer, placed in the position the Roman Pantheon reserved for the gods, surmounting the symbols of 19th-century deities – mining, industry, transport, trade, and capital – carved into stone escutcheons. While Lewis Mumford considered that the clock, rather than the steam-engine, was the key machine of the modern industrial age, for Austerlitz, and Peter Galison too, trains and clocks move forward together in the conquest of space and universal time, which was synchronised at the end of the 19th century according to the Greenwich meridian clock.

It comes as no surprise, then, that the first photograph of a timepiece that appears in Austerlitz is from the Royal Observatory in Greenwich and shows a British naval pocket watch associated with the Empire’s colonial history. The watch is barely recognisable because the image is so blurred. Twenty years have elapsed since the narrator’s first encounter with Austerlitz. Chance has brought them together in the Saloon Bar of the Great Eastern Hotel in London’s Liverpool Street Station in the midst of “the toilers in the City gold-mines”, and it is here that Austerlitz begins to piece together the story of his true origins from the information he has assembled over the years. Nor is it surprising that, on the following day, they walk as far as Greenwich and, in the observation room used by the former court astronomers, as he looks at the collection of sextants, quadrants, chronometers and clocks from the museum, Austerlitz embarks on a long impromptu digression about time – “the most artificial of all our inventions” –, with a list of unanswered questions that disprove the rational conjectures of science: “If Newton really thought that time was a river like the Thames, then where is its source and into what sea does it finally flow? (…) And is not human life in many parts of the earth governed to this day less by time than by the weather, and thus by an unquantifiable dimension which disregards linear regularity, does not progress constantly forward but moves in eddies, is marked by episodes of congestion and irruption, recurs in ever-changing form, and evolves in no one knows what direction?” He immediately goes on to say: “I have never owned a clock of any kind, a bedside alarm or a pocket watch, let alone a wristwatch. A clock has always struck me as something ridiculous, a thoroughly mendacious object perhaps because I have always resisted the power of time out of some internal compulsion which I myself have never understood…”

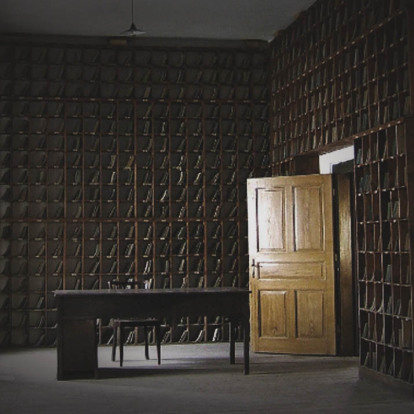

Small Fortress, Terezín (II). Dirk Reinartz (1995) / SEBALDIANA [cc]

, the first encounter in Antwerp station. A small clock marks time in the office of the archives Austerlitz visits in Prague and another features prominently in the foreground of a photograph of the room containing the files of the prisoners at Terezín, a photo that Austerlitz says he discovered at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris and is reproduced as a two-page spread. In the little office in Prague, a table covered with files seems to be waiting for him to find his mother’s whereabouts, while in the room at Terezín, the obsessive order of the records in their pigeonholes, the empty desks, the profusion of straight lines barely interrupted by the clock face, make up the doubly sinister, ominous backdrop of an infinite Babylonian library that the photo only partially depicts. For some reason, Sebald didn’t choose to include in his montage the view of the Small Fortress that Austerlitz may have taken at the Ghetto Museum, but the photograph by the German Dirk Reinartz, Small Fortress, Terezín (1995) which shows the clock at a right angle. This is one of the last images in the book and contrasts starkly with the one of the London office which appeared much earlier: a cramped, untidy room piled high with books and papers, where Austerlitz has tried to piece together the history of modern architecture. (143) The series of photos Sebald has interwoven into the story (the same ones Austerlitz says he arranged on the grey table top like a game of patience, moving them back and forth in “an order depending on their family resemblances “), begin to reveal the ghostly survivors of the modern world, like the interchangeable constellations of images in Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne-Atlas.

Barthes wrote at the end of Camera Lucida “I now know that there exists another punctum (another ‘stigmatum’) than the ‘detail.’ This new punctum, which is no longer of form but of intensity, is Time”. The book undoubtedly inspired Sebald. In Austerlitz, time is also the punctum of the montage, which not only tells the story of Jacques Austerlitz and the “that-has-been” of the Nazi extermination by the “in-between” placing of the images and texts. The tyranny of clocks that standardise and flatten time, the railway networks of the empires that speed up the production, consumption and unbridled exploitation by the colonies, the obsessive rationalism of bourgeois monumental architecture that is intensified at the Terezín archive, are the pricking stigmata of modern barbarism that long predates and goes beyond the holocaust. For Austerlitz and then Sebald, as it was earlier for Theodor Adorno and Hannah Arendt , modernity and the holocaust (the eloquent binomial coined by Zygmunt Bauman) are fatally interwoven. The path that leads to Auschwitz isn’t a uniquely German aberration, but a catastrophe anchored in modernity and the Enlightenment, and is, therefore, a threat that still persists. In order to forestall this threat and deny the tyrannical time of clocks, Sebald not only imagined the protracted encounter between a German storyteller and a Jewish historian, but also created a narrative form that slows down the present until it becomes porous to the glimmers of other times, troubles the reader with a fiction peppered with real images, brings it closer while moving it further away, and snatches it from the tide that pushes it forward and scatters it.

Graciela Speranza is an art critic, narrator and doctor of letters from the University of Buenos Aires, Argentina where teaches literature. Among other books she published: Primera persona. Conversations with fifteen Argentine narrators, Guillermo Kuitca. Obras 1982-1998, Razones intensas, Manuel Puig. Después del fin de la literatura, and the novel, Oficios ingleses. Collaborates with the cultural supplements of newspapers Page 12 and Clarín in Argentina, and El País (Babelia) in Spain. Her latest book Atlas portátil de América Latina was shortlisted for the 40th Anagram Essay Prize. She co-directs the magazine of letters and arts Otra parte.