On the natural history of translating Sebald

26 .05 .2015 - Miguel Sáenz

Translating is the most respectful form of reading. For me, translating Sebald involves reading him more carefully than I would otherwise have done. The only thing I regretted was not being able to translate all of Sebald. The translator is a strange being with an overweening sense of possession: not only does he want to translate somebody; he wants that somebody to be his. At any rate, Sebald once said, cheerfully mixing languages: “I always try to write for ceux qui savent lire”.

[Translated by Mark Waudby]

1. Sebald and his translators

Miguel Sáenz (Re-Photo / SEBALDIANA

Sebald was a man concerned about translation and, about the translation of his own works in particular. Not for nothing was he the founder of the British Centre for Literary Translation at the University of East Anglia. Moreover, although fluent in English, he always wrote in German because he didn’t consider his English was good enough.

He had the good fortune to work with some peerless English translators: Michael Hulse (a great poet), Michael Hamburger (a poet and friend too) and Anthea Bell, who is more than a match for her predecessors. However, the dissemination of Sebald’s work has been slow in other languages. The turning point came when he changed literary agent and his works were handled by Andrew Wylie, the most famous agent in the world. Wylie’s concern for the quality of the translations was even greater than Sebald’s and caused ructions at publishing houses, at least in Italy and Spain.

They offered me the chance to retranslate and revise The Emigrants, The Rings of Saturn and Vertigo, but I turned them down. Regardless of the fact that they were probably more than adequate translations, revising a translation gives you much more work than starting from scratch and the result satisfies no one. Today, Sebald’s translators form a veritable clan, thanks largely to the Italian Ada Vigliani. United by their veneration of the Master, they exchange messages about the works they are translating, highlighting problems, looking for solutions and pointing out inconsistences or errors.

I remember the fierce debate about the title of the book Schwindel. Gefühle (literally “Vertigo. Feelings”). The English version (no doubt with Sebald’s approval) was simply called Vertigo. The same occurred in Italian (Vertigi), French (Vertiges) and Spanish (Vértigo as Carmen Gómez titled it). Nevertheless, in Czech (Pocity. Závratĕ), Swedish (Svindel. Känslor) and Polish (Czuję. Zawrót glowy), the title has been translated more literally. The Finnish translator got upset because the publishers didn’t accept his Huimans/Tunteet, and shortened it to Huimans because they said that otherwise it would have looked odd. And the Hungarian translator got his own way by translating it exactly as Szédület. Érzés, although he had to drop the German plural (Gefühle) because széduletérzések would have been impossible.

2. Austerlitz

Sebald notes for the translator of Die Ringe des Saturn.

Austerlitz has been hailed as Sebald’s masterpiece and it unquestionably is. We find in it all the influences that Pablo D’Ors listed in his excellent critique: Kafka in the displacement of the character, Montaigne in its irony, Hesse in the love of nature, Bernhard in its syntax, Sarraute in the worship of objects, Sterne in the toing and froing of the narrator, Goethe in the eagerness to travel and unbaroque romanticism… Alan Pauls has, nonetheless, spoken of the unmistakeable “Sebald sentence”.

The book poses stylistic problems for the translator but its main difficulties concern research. For instance, you have to become a real expert in the construction of 18th- and 19th-century military fortresses. I had to consult Vocabulario militar by Brigadier D. Luis Corsini (1848), which I had inherited from my father, in order to familiarise myself with terms such as “escarpe” and “faussebraye”.

I also had to study moths and lunar maps, or find out about Lucas van Balkenborch, the painter of a famous Tower of Babel now on show in Frankfurt. Any translator of Sebald can spend days skipping from one website to another and feel very erudite, but with scant practical results.

And then there’s the problem of the footnotes. I have always been against them and am even more so today. The reader who wants to find something out can look it up on the internet. To give an example: Sebald quotes one of his favourite verses: “And so I long for snow to sweep across the low heights of London…“. In the German original, the text isn’t even in italics, but it would be easy for anyone to find out that it is a poem by Stephen Watts, a poet who has also been marked by migration who many English people discovered as a result of the quote in Sebald’s book.

3. Aerial warfare and literature

I really felt at home here because I had an in-depth knowledge of the Allied bombing raids on Germany. I had no hesitation in using, like the English, the title coined by Lord Zuckerman for an article he never wrote: On the natural history of destruction.

4. After Nature

Jan Hendricks (1), screen for unpublished book project “the natural”.

Nach der Natur (After Nature, clumsily translated by a certain Spanish publication as “Contra Natura” [“Against Nature“]), is what its author called “Ein Elementar Gedicht“, which I translated as Poema rudimentario, or rudimentary poem (“rudimentary” is a very Sebaldian word). I have never known if it is written in free verse or is a prose poem, but it is my favourite book by Sebald, certainly because of the challenges it poses to the translator.

It is divided into three parts: the first dedicated to Matthaeus Grünewald, a painter whose life we know little about (indeed, Coetzee has questioned some of Sebald’s assumptions); the second is devoted to an Arctic explorer, Georg Wilhelm Steller, who accompanied Vitus Bering on his last journey; and the third explores Sebald’s family history, culminating in his dream about a visit to the Alte Pinakothek art museum in Munich just to see Albrecht Altdorfer’s visionary painting The Battle of Alexander at Issus.

In truth, Nach der Natur doesn’t require as much research as Sebald’s other books, for the simple reason that the author already provides almost all the information. Only the reference to “another holy man from the Day of Judgement” with relation to a black eagle and a Pope would be cryptic to the reader who has no reason to know it alludes to one of the prophecies of Alois Irlmaier (1894-1959), who was a rather curious character.

The section about Georg Wilhelm Steller appears less brilliant, but it isn’t. At the beginning it reminded me of books read in childhood (Kenneth Robert’s Northwest Passage) and, above all, Christoph Ransmayr’s curious novel The Terrors of Ice and Darkness. In the latter, the author literally plundered historic documents to tell the story of an Austro-Hungarian expedition to the North Pole from 1872 to 1874, which is something Sebald doesn’t do.

Jan Hendricks was so enthused by the book that he created a series of silkscreen prints for a luxury edition. Unfortunately, the project didn’t come to fruition due to a failure to reach an agreement with Sebald’s heirs. Hendricks was generous enough to give me a full set of his beautiful prints.

5. Putrideces

The Spanish title of a selection of essays about Austrian literature, which showcase Sebald at his best, caused quite a stir among the Spanish publishing world: the German title is Unheimliche Heimat, a beautiful play on words which means weird or uncanny homeland. Pútrida patria (putrid homeland) replaced one play on words with another, but it went too far. The book contains some of W.G.M Sebald’s most intelligent (and harshly critical) writings.

6. Campo Santo

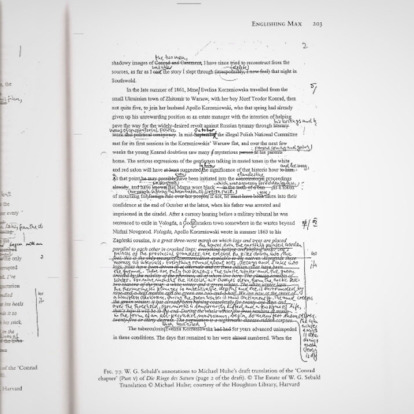

Jan Hendricks (2), screen for unpublished book project “the natural”.

How would you say “The bottom of the drawer” in French? The leftovers of the work by an author who has met an untimely death and which you have to use up? None of this applies here: in addition to fragments of an unfinished novel about Corsica, this book contains memorable essays. I particularly like the short acceptance speech to the Collegium of the German Language, which says: “For me, there is something strangely unreal about the entire Federal Republic, something like an endless déjà vu. Only a guest in England, I still hover between feelings of familiarity and dislocation there too. Once I dreamed, and like Hebel I had my dream in Paris, that I was unmasked as a traitor to my country and a fraud“.

7. A Place in the Country

The invitation to translate Logis in einem Landhaus (literally, “Accommodation in a house in the country”)came too late. I had been trying to give up translating for quite some time and was beginning to consider Sebald (quite wrongly as it turns out) as a brilliant writer who died too early to fulfil his promise. Moreover, I had no faith whatsoever in the Spanish public’s interest in the main characters of Logis – Rousseau, Keller, Mörike… As for Robert Walser, I had already translated, for another publisher, Sebald’s sensitive essay about him that was included in the book. (Curiously enough, the Italian edition had been similarly carved up).

I liked translating Sebald’s essay about Walser. Almost at the end, Sebald confesses his close affinity with him:

“I need only look up for a moment in my daily work to see him standing somewhere a little apart, the unmistakable figure of the solitary walker just pausing to take in the surroundings“.

Miguel Saenz Sagaseta de Ilurdoz (Larache, Morocco, 1932) is a translator of German authors, recognized with many awards. His work includes translations to Spanish of Bertolt Brecht, Günter Grass, WG Sebald and Thomas Bernhard, about whom he has written a biography. He has also translated from English novelists such as William Faulkner, Henry Roth and Salman Rushdie.